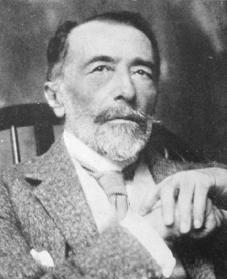

Was Conrad as antithetical to Dostoevsky as he supposed?

I have been reading Joseph Conrad’s attempt at a 19th century revolutionary Russian novel, Under Western Eyes. The book is considered Conrad’s riposte to Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and many of the devices and conclusions of that great novel are inverted and even satirised. Despite Conrad’s supposed detestation of Dostoevsky, however, I can’t help feeling that the two novelists perhaps had more in common than the Pole might acknowledged and their treatment of common themes in their novels may not have diverged as radically as he believed.

I have been reading Joseph Conrad’s attempt at a 19th century revolutionary Russian novel, Under Western Eyes. The book is considered Conrad’s riposte to Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and many of the devices and conclusions of that great novel are inverted and even satirised. Despite Conrad’s supposed detestation of Dostoevsky, however, I can’t help feeling that the two novelists perhaps had more in common than the Pole might acknowledged and their treatment of common themes in their novels may not have diverged as radically as he believed. Joseph Conrad was born in what is currently modern Ukraine (then part of the Russian Empire) into a passionately nationalist family of Polish aristocrats. Indeed his father was arrested by the Tsarist authorities for his involvement in the movement which would foment the 1863 January Uprising by citizens of the Polish – Lithuanian Commonwealth. His father’s arrest and exile, coupled with the subsequent premature deaths of both his parents, is generally held to have contributed to Conrad’s dim view of Russians and the Russian state. It must also have informed the antipathy towards revolutionary movements, whose intemperance he believed swallowed up the lives of those they touched, which is very much evident in Under Western Eyes.

Conrad’s dislike of Dostoevsky sprang from the Pole finding his antecedent ‘too Russian’. In contrast he admired the westerniser Turgenev. It's ironic then that Conrad’s revolutionaries owe more to the preening, conceited, mutually self-sustaining extremists in ‘Devils’ than the genuinely remarkable nihilist Bazarov, whom Turgenev portrayed in ‘Fathers and Sons’.

Under Western Eyes assumes not only the structures of Crime and Punishment, but its imagery is also redolent of the older novel. To take an obvious example, both books draw heavily on images of ghosts and spectres. Both Razumov and Raskalnikov encounter visions of their respective victims (in Razumov's case his supposed victim). Conrad’s ‘a moral spectre is infinitely more effective than any visible apparition of death' can be read as a direct interpretation of Dostoevsky’s work. Although Conrad inverts Crime and Punishment, Razumov’s journey of conscience bears striking resemblance to that of Raskalnikov and whilst the moral odyssey does not end in the same place, both writers take their characters along a similar route.

In terms of motivation and self-conception, Razumov is a strikingly different character to Raskalnikov. Raskalnikov views himself as a ‘Napoleon’, entitled by providence to set aside conventional morality in order to perform remarkable acts. In contrast Razumov wishes to pursue a much quieter route. He has no preconceptions about achieving greatness or effecting change. He wishes instead to excel at his studies and achieve whatever degree of prominence he can through coventional routes.

Dostoevsky’s protagonist, fuelled by conceit and self-regard, commits a pathetic act of murder in order to prove to himself how exceptional he is and discovers instead that he suffers from conscience just as acutely as most other people. It is others who thrust the conception of exceptionalness unto Conrad’s anti-hero, who suffers no such pretence, and it is this burden which frames his moral dilemma. Razumov’s crime is in itself a ‘phantom’, or at least it is in the minds of the various revolutionary students of St Petersburg and the émigrés he encounters in Geneva. Nevertheless the internal struggle which he faces leads him to much the same place as Raskalnikov, burdened with remorse and asking, ‘do I suffer from conscience just like anyone else’? Albeit it is a secular / humanist mode of thinking which brings Razumov to this place, rather than the discovery of Christian humility which Raskalnikov experiences.

Conrad’s novel undoubtedly bristles with antipathy toward Russia at times. His narrator, an aging English teacher of languages, voices many generalisations on the Russian character and the incurable nature of Russian despotism. Admittedly Dostoevsky, and indeed a vast swathe of golden age Russian writers, were quite happy themselves to discourse in broad strokes on the make-up of Russian national character. Dostoevsky viewed the Russian 'curse' as primarily a western import which the country would throw off, to return to a prelapsarian state. Conrad's Russian curse is in contrast something intrinsic to its people and their character. Both however offer similarly binary, if diametrically opposed, interpretations of Russia's woes. There are conservative traits to both the writing of Conrad and the work of Dostoevsky, both of whom ultimately frown on the rash nihilist impulse.

Conrad is equally scathing of both the absolutist monolith which rules pre-revolutionary Russia and the revolutionists who wish to bring it crashing down. Dostoevsky’s initial revolutionary sympathies were tempered by a belief that Russia’s course should be separate from the west and that Orthodoxy and tsarism played essential roles in shaping and sustaining a unique Russian identity. Razumov initially views himself as a liberal, but when confronted with direct action against despotism he is forced to acknowledge his convictions are framed by the assumption that strong, centralised rule is necessary for Russia. Raskalnikov ultimately seeks redemption through religion which reveals its power through the love of Sonya. Although Conrad despised Raskalnikov's conversion, interpreting it as a symptom of a brand of mysticism, which was the disease rather than the cure, his own character also eventually finds a similar type of stoical balance.

Despite Conrad’s intention to write Under Western Eyes in opposition to Crime and Punishment, it is a remarkably Dostoevskyian novel. Both works are also as relevant today as when they were first written. Crime and Punishment might have been anticipating the psychology behind any number of crimes and criminals from the last two centuries. Conrad’s observations about revolutions remain strikingly pertinent, indeed almost prophetic.

“A violent revolution falls into the hands of narrow minded fanatics and tyrannical hypocrites. The scrupulous and the just, the noble, humane and devoted natures, the unselfish and the intelligent may begin a movement but it passes away from them.”

A fierce antipathy toward Dostoevsky may have inspired Conrad’s novel, but nevertheless that writer’s work informed Under Western Eyes in ways which are not antithetical. Despite the difference in outlook between these writers they share more than divides them.

Comments

t3n

flythemes

oneplus

dignitas

What is the True Meaning of a Pinky Promise

gitter

gajim

That said, I would like to know more about what we know of Conrad's stated intentions for the novel. The blog's author states with confidence that Conrad intended to refute Dostoyevsky or be an antithesis of him - and he is not alone in stating this. But I am not familiar enough with the sources available and would like to know in what way, precisely, Conrad meant to refute or correct Dostoyevsky. As the blogger rightly points out, there is too much in common with the moral arcs of their two novels, too much in common in the contempt for both autocrat and revolutionary, for Conrad to have meant to refute him in any kind of simple way.

When the blogger points out the difference in their diagnoses for Russia, i.e., Dostoyevsky's assessment of the disease as being a Western one with a spiritual cure whereas Conrad sees it as inherently Russian and requiring only more secular reason (Razum), he is very persuasive.

Nonethless, I would like to better understand the nervous breakdown Conrad underwent writing this, the role of his childhood and his own father in his feelings of betrayal, and how he would have read Dostoyevsky's "too Russian"-ness. Could perhaps he have meant that Dostoyevsky was a genius who had truly painted a true picture, but it just needed correcting on its margins? Would a such a critique of a few datails of Dostoyevsky's approach have been worthy of an entire novel that otherwise walks in Crime and Punishment's shadow throughout? Was such a dubious effort made more worthy to the author by his own personal history alone or is there some kind of blame for Dostoyevsky and some level of the moral critique of Dostoyevsky that was of the utmost importance to Conrad but that is perhaps simply not easy to decipher to readers today?

I still have so many questions but I am grateful to this blogger for this effort to grapple with these questions and I hope he will continue to do so. As for me, I'm off to read Crime and Punishment again to see what I may have missed the first time, so many years ago. I am certain it is a lot...

goyard bag

chrome hearts outlet